The student's guide to independence in R

Contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. How do I get started?

- 3. Common analysis steps

- 3.1. I. Reading raw data

- 3.1.1. An aside about file paths

- 3.2. II. Cleaning up and preprocessing raw data

- 3.3. III. Aggregate raw data

- 3.4. IV. Descriptive analysis and plots

- 3.4.1. Descriptive stastics: Getting a sense of your data

- 3.4.2. Confidence intervals

- 3.4.3. Data visualisation magic

- 3.4.3.1. Boxplots

- 3.4.3.2. Adding titles and labels

- 3.4.3.3. Spaghetti plots

- 3.4.3.4. Fancy Barplots

- 3.4.3.5. Visualizing correlations with scatter plots

- 3.5. V. Inferential analysis

- 3.5.1. Normality assumption

- 3.5.2. Homogeneity of variance assumption

- 3.5.3. Correlation

- 3.5.4. Regression

- 3.5.5. t-test

- 3.5.6. One-way ANOVA

- 3.5.7. Repeated measures ANOVA

- 3.5.8. Mixed designs (within/between factors)

- 3.1. I. Reading raw data

- 4. General notes on

R|

Introduction

Dear students,

This tutorial was developed for thesis students at LISCO lab (Lifespan Brain and Cognitive Development lab, Goethe-University Frankfurt am Main) and may also be useful in other contexts.

In this tutorial, I - Dr. Sophie Nolden - will provide some tips that are meant to help you to use R independently. This implies that you find own solutions for your analyses, with operations and functions that are new to you. If you are students at Goethe-University, most of you have already worked with R in the Expra or other courses, and things may have seemed very clear to you back then. However, when you have to create your own analysis script from scratch, you may sometimes be a little lost. I thus summarized a few key points that can help you to find your way in the jungle!

Please make sure that you always try to figure out the solution yourself first. If you are stuck, ask your peers (or your supervisor if your peers cannot help you), and make sure that you provide all the information needed to understand both your question and your first approach to solve the problem.

Enjoy reading!

You should be familiar with some basics in R before you continue, have a look at these notes, for example.

If you need more input, I suggest to work with an online tutorial of your choice. For example, check out these three (1, 2, 3) suggestions on first steps in R.

You may also want to checkout the documentation on R Markdown.

The Department of Psychological Methodology at the Psychology Faculty of Goethe-University has also created pandaR - the very site you are reading this tutorial on. pandaR was first created in order to present projects to deepen your skills in R and to experiment around with the contents of the module PsyBSc2 that aims to teach students the statistical basics in R. Since then, the team has worked on uploading detailed tutorials on various statistical measures and applications. Have a look at the page Lehre where you can find an overview of all the topics that are dealt with in the statistics lectures.

On pandaR you’ll find a general introduction to R that offers a very detailed explanation of the most important functions of the software (in German). Feel free to take a look, if you are new to R!

You should now know the following concepts (please test yourselves):

- What is a data frame? How is it different from a matrix?

- How can I access certain data points in a data frame? How can I select certain rows or columns?

- Which classes of data are there?

- What is a function and how is a function different from a script?

- What is a boolean expression?

- Why are there different packages? How can I install packages?

How do I get started?

Before you write your first line of R code, make sure that you know exactly what you would like to do and how you want to do it.

Here are some examples for very general questions: Do you want to calculate an average? Do you want to calculate a t-test or rather a correlation? What are your independent and dependent variables?

Once your general approach is clear, ask yourself more specific questions such as: In which columns of my data frame do I find my independent or dependent variables? Do I want to correct for outliers? Which lines should be deleted if I want to exclude practice blocks?

Just imagine your data frame was a table on a physical sheet of paper and your only tools were a pen and a simple calculator. What would be your analysis steps?

Very often, students tell me that they do not know how to handle R, but once I start asking questions about their analysis plan, I realize that they actually do not know what they want to do! So make sure that every single step of your analysis is clear to you. I suggest to write down your analysis steps into your script (as comments). Once you are done and your concept makes sense to you, you can fill it up with actual code. This way, you have already made sure that your documentation is well done, since there should be a balance of 50:50 between comments and code.

Generally speaking, your script should be structured like this:

- Start your script with a title, your name, and the current date. If your script is based on an older script, provide this information as well.

- Clean up your global environment.

rm(list = ls())

- Continue with your parameters. These are values that you may eventually want to change and that you do not want to search for in every single line of your script. For example, you write your data path here, or you define the different age groups that you have tested. Just make sure you write your script in such a way that you can use it at multiple occasions (which may become relevant for your thesis).

- Continue with your actual analysis. Provide some structure and comment on everything you do. Documentation is important so that the script is understandable for others, both your collaborators and your future self.

Where can I get help?

After you gained some basic knowledge in R, you should definitely not expect to sit down in front of your computer and then, magically, your fingers just type down all the code. It is a matter of constant improvement, and you will have to learn how to use new functions all the time!

It is normal to look up how to do certain things, even if you have dealt with a similar problem before.

Here are four main sources of help for your script:

- Recycle elements from previous scripts. Create functions for recurring problems. This is actually quite useful because you have already figured it out once before. Remember to always provide comments on what you are doing in the script, in order to be able to recycle stuff in the future.

- Use a search engine of your choice and look up your question in the internet. The community is huge and usually very friendly, and chances are quite high that somebody else has encountered your problem before. (You can also post questions yourself if nobody has asked your questions before, but this will most likely not be the case.) Search in English. I like pages such as

stackoverflowandgithubfor helpful discussions. It will take some time until you know how to ask your questions properly. Your first search term should of course be “R”. Use key words fromRand psychology, such as “data frame”, “columns”, “outlier”… If you put too many terms into the search window, you will probably get a lot of results that are not related to your question, so try to be precise. When you realize that the answers you get are rather remote from what you actually want, change your search terms. - Use the help function in

R. This requires some practice and may not always help you when you are new to it. I find it most useful for the list of input arguments and the examples provided in the end. - As mentioned before, you will find many detailed tutorials on specific statistical topics on pandaR.

This is how you deal with the help function.

help(<function>)

?<function>

help.start()

Use apropos(<topic>) in case you do not know the name of a specific function.

apropos('anova')

## [1] "anova" "manova" "power.anova.test" "stat.anova"

## [5] "summary.manova"

Use example(<topic>) if you want to see an example.

You can copy the code for any boxplot example from your console and run it or you can press enter to get a new example. Type stop() when you’ve had enough and you can go back to running new code.

Common analysis steps

All analyses are of course different, but there are some common analysis steps that we encounter most of the time:

- Reading raw data

- Cleaning up and preprocessing raw data

- Aggregating raw data

- Descriptive analysis and plots

- Inferential analysis

We will go through them step by step.

I. Reading raw data

Getting error messages in R can be frustrating at the beginning. However, it is quite normal, and you will learn to read the error messages in a way that they can guide you to the solution. Not handling your raw data properly, on the other hand, can lead to REAL PROBLEMS!!!

You have to be super careful with your raw data. Store it at multiple sites on different drives. And NEVER, really NEVER EVER, write into your raw data directory. This is why we call our raw data directory sometimes “Holy Folder”, and it must NEVER be touched other than for reading the data so that you can never accidentally overwrite it.

That is why we need an “in_path” and an “out_path”, one directory to read from, one to write into. Create a directory with all participants’ raw data. If you already know that you want to exclude a participant for whatever reason, you can already omit the respective file at this stage. Create a directory called “Analyses” or something similar. Always choose meaningful names and avoid spaces or special characters.

# Define in_path.

in_path <- "/home/soph/Documents/thesis/Holy_Folder/"

# Define out_path.

out_path <- "/home/soph/Documents/thesis/Analyses/"

in_path

## [1] "/home/soph/Documents/thesis/Holy_Folder/"

out_path

## [1] "/home/soph/Documents/thesis/Analyses/"

It is very common that there are errors in your paths. In order to avoid typos, I suggest that you browse to your directory and then copy the path from there (e.g., from your browser header, or by selecting the properties of a file in that directory). This can be especially helpful for long and complicated paths. If you use Windows, you may need to change the slashes. R only recognizes forward slashes, therefore you have to replace all backwardslashes. Try Ctrl + F; in the search bar you can “find” all backslashes and “replace” them with forward slashes by clicking on “All” on the very right of the bar.

Make sure that you do not forget the " “.

And, last but not least, and that is very often overlooked by beginners: Do not forget the last slash in the end! ;-)

You can also set your working directory in R via “Session” -> “Set Working Directory” (to your out_path).

I recommend to never use spaces or special characters in your path. It may be worthwhile renaming your directories. The same is true for all objects/column names/characters you create in R. It is not impossible to handle spaces in R, but it is definitely more troublesome.

Remember that your paths should be defined at the beginning of your file.

An aside about file paths

As you begin using R in more of your projects, some of which may involve collaboration, you may begin to notice that dealing with paths and working directories can get, well, pesky. An example: your colleague Bailey sends you a folder with their data and analysis scripts. In the script, they begin with setting the working directory using:

setwd("C/Users/bailey/Documents/projectA/analysis/")

Or at various points in the file, they load data using:

load("C:/Users/bailey/Documents/projectA/analysis/somefolder/blahblah.rda")

It’s easy to see how the specificity of file paths can quickly get annoying and make the script fragile. You are not Bailey, so you will have to change all of the paths in the files for the script to work again. And what if you were working on a script but then you get a new computer? What if you forgot one tiny “/” and now you want to set your computer on fire? And so on and so on.

A package that offers answers to these issues is the here() package. Combined with a logical folder structure, here() can improve the flexibility of your scripts so that neither you nor your collaborators will have to rename another file path again. Anywhere you would use “C:/filepath/blahblah”, you can replace with here(). You can check out a straightforward guide to using it here (no pun intended).

Let’s have a look at a few cases that you may run into

- We very often read data from

.csvfiles. There are specific functions for reading.csvfiles that you can use. I personally prefer the functionfreadbecause it can handle various data types quite easily.

This is how you can read all your participants’ data files into one data frame at once:

library(data.table) # fread is part of the library "data.table".

filenames <- list.files(inPath, pattern="*.csv", full.names=TRUE) # Create a list of your data files.

myData <- rbindlist(lapply(filenames,fread),fill=TRUE) # Read in your data files and concatenate them to one big data frame.

- Sometimes, you may need to open data files saved with

SPSS.SPSSis a commercial software and not everybody may have the license installed, so it can be quite tricky to open these kinds of files. I suggest to use the packagehavenfor this matter.

library(haven) # This library is useful to deal with SPSS files.

SPSSfile <- "myOtherData.sav" # Define the name of your SPSS file.

myOtherData <- read_sav(paste(inPath, SPSSfile, sep = "")) # Read in SPSS data. Note how I used "paste" to concatenate two character values (your path name and your file name).``

- If you tested multiple groups (e.g., children, young adults, and older adults), you may want to organize their data in different folders. In this case, I recommend to loop through these folders and add up all files into one single data frame. Just provide a vector of character values as “in_path”, with each character vector representing one path.

# Define in_path.

in_path <- c("/home/soph/Documents/thesis/Holy_Folder/Child/"

, "/home/soph/Documents/thesis/Holy_Folder/YA/"

, "/home/soph/Documents/thesis/Holy_Folder/Child/OA/")

Next, create an empty data frame with the same amount of columns and the same column name as in your actual raw data.

all_groups <- setNames(data.frame(matrix(ncol = 9, nrow = 0))

, c("participant", "group", "age", "sex", "handedness"

, "IV1", "IV2", "DV1", "DV2"))

Loop through the different directories and read the data from each directory one after another (e.g., into a data frame called “my_data”). Add it all to your empty data frame at the end of each iteration.

all_groups <- rbind(all_groups, my_data)

Tip 1 for using loops: Restrict the use of loops to a minimum, since R is not really fast dealing with loops (but it will do it eventually).

Tip 2 for using loops: Use a meaningful term for the value that changes at each iteration. “val” or “i” are not meaningful, but “i_group” or “i_participant” are. This will help you to keep track of what you are actually doing, especially in nested loops.

If you are interested in finding out more about loops and the (literally) endless possibilites that they offer, you can check out the tutorial on them on pandaR.

- In some cases, multiple files are generated per participant and you may want to merge the different files. For example, in a memory study, you have one file for a memory encoding session and one file for a memory retrieval session. It can be useful to have the two sessions organized as different columns and each line referring to a specific stimulus. In this case, check out a “merge” function (I like the one from the package “data.table”) in these cases.

Once your data are all in, you should take some time to check if all data looks as it is supposed to be. Are all subjects there? Is the number of lines as expected (this is very often the number of trials by the number of participants)? Are all conditions there? Is the number of trials for each condition correct?

For this purpose, use the table function. Have a look at your “global environment” as well where you can see the dimensions of your data frame.

If you still have questions about loading your data into R or if you’re still unsure on how the working directory works, have a look at the R crash course on pandaR, where all these topics are discussed in more detail.

II. Cleaning up and preprocessing raw data

Our raw data files are usually organized such that one line contains all information from one trial. However, there may be trials that we do not need, such as practice trials. Or there may be empty lines between blocks that we also do not need.

Let’s have a look at the following example:

# Let's create a little example data frame.

example1 <- setNames(data.frame(matrix(ncol = 5, nrow = 10))

, c("participant", "OS", "block_number", "DV", "IV"))

# Values in columns.

example1[1:5,1] <- 5

example1[6:10,1] <- 6

example1[,2] <- as.character("Windows")

example1[,3] <-c(NA,1,1,2,2,NA,1,1,2,2)

example1[,4] <- c(.5,.6,.7,.7,.8,.9,.9,.8,.5,.7)

example1[,5] <- c("B","A","B","B","A","B","B","A","B","A")

example1

## participant OS block_number DV IV

## 1 5 Windows NA 0.5 B

## 2 5 Windows 1 0.6 A

## 3 5 Windows 1 0.7 B

## 4 5 Windows 2 0.7 B

## 5 5 Windows 2 0.8 A

## 6 6 Windows NA 0.9 B

## 7 6 Windows 1 0.9 B

## 8 6 Windows 1 0.8 A

## 9 6 Windows 2 0.5 B

## 10 6 Windows 2 0.7 A

Side note: if you want to learn more about creating data frames, have a look at our R crash course, starting from the block “Daten”.

The column “block_number” contains, well, the block number. Lines with NA are practice trials. We can remove them like this:

example1 <- example1[!is.na(example1$block_number),] # Check the different parts of this line. What do the "!" and "is.na" do? Also check out the position of the comma in the square brackets. Remember: Rows first, columns later on!

example1

## participant OS block_number DV IV

## 2 5 Windows 1 0.6 A

## 3 5 Windows 1 0.7 B

## 4 5 Windows 2 0.7 B

## 5 5 Windows 2 0.8 A

## 7 6 Windows 1 0.9 B

## 8 6 Windows 1 0.8 A

## 9 6 Windows 2 0.5 B

## 10 6 Windows 2 0.7 A

We probably also want to remove the column “OS” because it is not very helpful here. You can select specific columns by index or name, and you can also delete specific columns.

The following three code chunks do the same thing:

example1_copy <- example1 # Let's create a copy of example1 so we can do the same stuff over and over again.

example1 <- example1[,c(1,3,4,5)] # Select certain columns by index. Check out the position of the comma.

example1

## participant block_number DV IV

## 2 5 1 0.6 A

## 3 5 1 0.7 B

## 4 5 2 0.7 B

## 5 5 2 0.8 A

## 7 6 1 0.9 B

## 8 6 1 0.8 A

## 9 6 2 0.5 B

## 10 6 2 0.7 A

example1 <- example1_copy # Back to our previous data frame.

example1 <- example1[,c("participant", "block_number", "IV", "DV")] # Select certain columns by name.

example1

## participant block_number IV DV

## 2 5 1 A 0.6

## 3 5 1 B 0.7

## 4 5 2 B 0.7

## 5 5 2 A 0.8

## 7 6 1 B 0.9

## 8 6 1 A 0.8

## 9 6 2 B 0.5

## 10 6 2 A 0.7

example1 <- example1_copy # Back to our previous data frame.

example1$OS <- NULL # Delete a single columns by its name.

example1

## participant block_number DV IV

## 2 5 1 0.6 A

## 3 5 1 0.7 B

## 4 5 2 0.7 B

## 5 5 2 0.8 A

## 7 6 1 0.9 B

## 8 6 1 0.8 A

## 9 6 2 0.5 B

## 10 6 2 0.7 A

Actually, this would also be a good moment to organize the order of your columns in a more useful way. I prefer to start with the participant number, the group, time of testing, personal information like age and gender, information on stimuli, independent variables, and dependent variables in the end.

In the example above, it could be nice to switch the position of the independent and dependent variable.

The following two code chunks do the same thing:

example1 <- example1_copy # Back to our previous data frame.

example1 <- example1[,c(1,3,5,4)] # Omit the second block and switch the two last blocks.

example1

## participant block_number IV DV

## 2 5 1 A 0.6

## 3 5 1 B 0.7

## 4 5 2 B 0.7

## 5 5 2 A 0.8

## 7 6 1 B 0.9

## 8 6 1 A 0.8

## 9 6 2 B 0.5

## 10 6 2 A 0.7

example1 <- example1_copy # Back to our previous data frame.

example1 <- example1[,c("participant", "block_number", "IV", "DV")] # Or use the variable names.

example1

## participant block_number IV DV

## 2 5 1 A 0.6

## 3 5 1 B 0.7

## 4 5 2 B 0.7

## 5 5 2 A 0.8

## 7 6 1 B 0.9

## 8 6 1 A 0.8

## 9 6 2 B 0.5

## 10 6 2 A 0.7

Sometimes, you need to calculate new variables. Imagine the participants’ task was to indicate if a letter was a vowel or a consonant with a left or a right key press. Imagine also that the response mapping was counterbalanced, hence, half of the participants were supposed to respond to a vowel with a left key press and to a consonant with a right key press whereas the other half of the participants had the reversed mapping. Your software may have recorded whether the participants responded with a left or a right key press at a given trial, but not necessarily if participants wanted to indicate that they saw a vowel or a consonant, and if their response was correct. Let’s check out how we could create new variables in this case.

Let’s create another little example data frame.

# Let's create a little example data frame.

example2 <- setNames(data.frame(matrix(ncol = 4, nrow = 8))

, c("participant", "stimulus", "counterbalancing", "response"))

# Values in columns.

example2[1:4,1] <- 1

example2[5:8,1] <- 2

example2[,2] <- c("V","C","C","V","C","V","C","V")

example2[,3] <-c("vowel_left", "vowel_left", "vowel_left", "vowel_left", "cons_left", "cons_left", "cons_left","cons_left")

example2[,4] <- c("l", "r", "l", "l", "l", "l", "r", "r")

example2

## participant stimulus counterbalancing response

## 1 1 V vowel_left l

## 2 1 C vowel_left r

## 3 1 C vowel_left l

## 4 1 V vowel_left l

## 5 2 C cons_left l

## 6 2 V cons_left l

## 7 2 C cons_left r

## 8 2 V cons_left r

Let’s first calculate a new variable that contains the meaning of the response.

example2$response_type <- "V" # As a default we put vowel.

example2$response_type[example2$counterbalancing == "vowel_left" & example2$response == "r"] <- "C" # If the participant is supposed to indicate consonants with the right response (belongs to the first counterbalancing group) and responded with the right key.

example2$response_type[example2$counterbalancing == "cons_left" & example2$response == "l"] <- "C" # If the participant is supposed to indicate consonants with the left response (belongs to the second counterbalancing group) and responded with the left key.

example2

## participant stimulus counterbalancing response response_type

## 1 1 V vowel_left l V

## 2 1 C vowel_left r C

## 3 1 C vowel_left l V

## 4 1 V vowel_left l V

## 5 2 C cons_left l C

## 6 2 V cons_left l C

## 7 2 C cons_left r V

## 8 2 V cons_left r V

Let’s calculate accuracy as well: 0 = incorrect response, 1 = correct response.

example2$accuracy[(example2$stimulus == "V" & example2$response_type == "V") | (example2$stimulus == "C" & example2$response_type == "C")] <- 1 # Let's find the cases where stimulus and response_type match. Have a look at how I combined logical "and" and "or" and how I used brackets here.

example2$accuracy[is.na(example2$accuracy)] <- 0 # Now let us fill up with zeros for the incorrect responses.

example2

## participant stimulus counterbalancing response response_type accuracy

## 1 1 V vowel_left l V 1

## 2 1 C vowel_left r C 1

## 3 1 C vowel_left l V 0

## 4 1 V vowel_left l V 1

## 5 2 C cons_left l C 1

## 6 2 V cons_left l C 0

## 7 2 C cons_left r V 0

## 8 2 V cons_left r V 1

Once again, check if all data are as they are supposed to be! The table() function helps you here.

If everything looks good, this would be a good moment to save your data frame to disk, e.g., in a .csv file.

III. Aggregate raw data

Aggregating means summarizing your data. For example, you may be interested in averaging all trials of each condition and each participant. For example, if you have two conditions, you may want to average all trials such that there are two averages per participant in the end, one for each condition.

Sometimes, we need to exclude outliers before we average raw data. For example, when you average response times, very slow responses may bias your averages strongly. You do not want to include these response times in your analysis. This is how you can proceed:

- Use the function “group_by” of

dplyrto group your data frame by participant. This could look like this:

my_data <- group_by(my_data, participant)

You may be disappointed: Your data frame looks as it has looked before. However, all consecutive commands will be executed within the trials belonging to the same participant. Later, use ungroup if you do not want grouping anymore.

- Create a new column that contains your z-transformed response times. There are plenty of ways to do the z-transform. I like the function

scale(). - Delete all rows that contain a z-value that exceeds your criterion (e.g., 3). You already know how to do this! Check out the “clean up raw data” section for inspiration!

In a similar way, you can also remove very fast responses, e.g. < 50 ms. In this case, you can work directly with the raw response times, no need for transforms!

Let us continue. I will provide an example data frame for you with one between IV, one within IV, and accuracy as DV:

example3 <- setNames(data.frame(matrix(ncol = 4, nrow = 12))

, c("participant", "IV1", "IV2", "accuracy"))

# Values in columns.

example3[1:6,1] <- 5

example3[7:12,1] <- 6

example3[,2] <- c('r','r','r','r','r','r','s','s','s','s','s','s')

example3[,3] <- c('B','A','A','B','A','B','A','B','A','A','B','B')

example3[,4] <- c(0,1,1,0,0,1,1,1,1,1,0,1)

example3

## participant IV1 IV2 accuracy

## 1 5 r B 0

## 2 5 r A 1

## 3 5 r A 1

## 4 5 r B 0

## 5 5 r A 0

## 6 5 r B 1

## 7 6 s A 1

## 8 6 s B 1

## 9 6 s A 1

## 10 6 s A 1

## 11 6 s B 0

## 12 6 s B 1

When you create your script, you need to test it very carefully. Thus, when you work on the data aggregation, I strongly recommend to use an example data frame as the one above to try if everything works as you want it to work. Your raw data frame will very likely contain thousands of lines and chances are high that you would miss out on errors if you worked with the entire raw data frame.

You do not necessarily need to create a completely artificial example data frame. You can also select a limited amount of lines from your “real” raw data, e.g., you select two participants and for each participant 5 trials of all possible conditions. Just make sure that you think of all possible combinations of relevant variables when creating your example raw data frame.

Let us turn to the actual aggregation. I recommend the function “aggregate” from “stats”:

# Aggregate data (summarize over the within IV, separate for each participant).

agg_example3 <- aggregate(example3$accuracy # Which variable should be aggregated?

,list(example3$IV1,example3$participant,example3$IV2) # How should we split up the new data frame?

,mean) # What is our actual operation?

agg_example3

## Group.1 Group.2 Group.3 x

## 1 r 5 A 0.6666667

## 2 s 6 A 1.0000000

## 3 r 5 B 0.3333333

## 4 s 6 B 0.6666667

The column names do not look especially fancy, so let us rename them.

# Create sensible column names.

colnames(agg_example3) <- c('IV1'

,'participant'

,'IV2'

,'accuracy') #Name the columns with a vector containing the labels.

agg_example3

## IV1 participant IV2 accuracy

## 1 r 5 A 0.6666667

## 2 s 6 A 1.0000000

## 3 r 5 B 0.3333333

## 4 s 6 B 0.6666667

We can now arrange the data frame the way we want, just as we did it with the raw data.

# Re-order columns.

agg_example3 <- agg_example3[,c(2,1,3,4)]

# Sort lines.

agg_example3 <- agg_example3[order(agg_example3$participant),]

agg_example3

## participant IV1 IV2 accuracy

## 1 5 r A 0.6666667

## 3 5 r B 0.3333333

## 2 6 s A 1.0000000

## 4 6 s B 0.6666667

When the aggregation of your example data frame works correctly, turn to the real raw data. Once you’re done, check again if everything worked correctly. I suggest that you think of all possible cases/constellations and check if they worked for a few randomly selected subjects.

Again, the table() function is your friend here!

Once you have aggregated your raw data, you may still need to do a few adjustments to your data frame in order to get prepared for your further analyses.

One common dependent variable we use in memory research is the recognition probability (Pr) in recognition tests. This is the difference of hit rates and false alarm rates. Sometimes, we have different conditions during learning (e.g., expected or surprising objects) and thus, you end up with hit rates for expected and surprising objects. If your new objects do not allow you to separate between expected and surprising objects, there will be just one type of false alarm rate. We can still calculate Pr by using the hit rates of each condition and subtracting the same false alarm rate in both cases. I will show you how:

We first create an example data frame (already aggregated).

# Now something a little more realistic.

example4 <- setNames(data.frame(matrix(ncol = 3, nrow = 6))

, c("participant", "stim_type", "accuracy"))

# Values in columns.

example4[1:3,1] <- 5

example4[4:6,1] <- 6

example4[,2] <- c('exp','sur','new','exp','sur','new')

example4[,3] <- c(.5,.6,.7,.7,.8,.9)

example4

## participant stim_type accuracy

## 1 5 exp 0.5

## 2 5 sur 0.6

## 3 5 new 0.7

## 4 6 exp 0.7

## 5 6 sur 0.8

## 6 6 new 0.9

Let us group participants because everybody has an individual false alarm rate.

library(dplyr) # This library is our friend for so many things! Remember to install the package beforehand, if you have never used it before!

# Group by participants (use "ungroup" to remove all grouping).

example4 <- group_by(example4, participant)

And now, let us calculate Pr. Do not forget that, for new items, we currently have accuracy, not false alarm rate.

# For false alarm rates, we use 1 - the value in the third row. Thanks to grouping, this is done individually for all subjects.

example4 <- mutate(example4, Pr = accuracy - (1-accuracy[3])) # mutate is also a nice and useful function.

example4

## # A tibble: 6 × 4

## # Groups: participant [2]

## participant stim_type accuracy Pr

## <dbl> <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 5 exp 0.5 0.2

## 2 5 sur 0.6 0.3

## 3 5 new 0.7 0.4

## 4 6 exp 0.7 0.6

## 5 6 sur 0.8 0.7

## 6 6 new 0.9 0.8

Pr values for new items do not make any sense, remove values, so let us remove them.

example4$Pr[example4$stim_type == "new"] <- NA

example4

## # A tibble: 6 × 4

## # Groups: participant [2]

## participant stim_type accuracy Pr

## <dbl> <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 5 exp 0.5 0.2

## 2 5 sur 0.6 0.3

## 3 5 new 0.7 NA

## 4 6 exp 0.7 0.6

## 5 6 sur 0.8 0.7

## 6 6 new 0.9 NA

Or remove the line with new items

example4 <- example4[!example4$stim_type == 'new',]

example4

## # A tibble: 4 × 4

## # Groups: participant [2]

## participant stim_type accuracy Pr

## <dbl> <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 5 exp 0.5 0.2

## 2 5 sur 0.6 0.3

## 3 6 exp 0.7 0.6

## 4 6 sur 0.8 0.7

At this point, it is also good to check participants’ performance. Do you want to exclude participants with low performance?

Double check again if your data frame is as it is supposed to be. If so, you are all set for your further analyses!

IV. Descriptive analysis and plots

Descriptive stastics: Getting a sense of your data

For exemplary descriptive analyses, let’s stick to the previously mentioned example data frame. But we extend it a little bit to get more data points.

example5 <- setNames(data.frame(matrix(ncol = 3, nrow = 12))

, c("participant", "stim_type", "Pr"))

# Values in columns.

example5[1:2,1] <- 5

example5[3:4,1] <- 6

example5[5:6,1] <- 7

example5[7:8,1] <- 8

example5[9:10,1] <- 9

example5[11:12,1] <- 10

example5[,2] <- c('exp','sur','exp','sur','exp','sur','exp','sur','exp','sur','exp','sur')

example5[,3] <- c(.11, .3, .13, .5, .21, .99, .08, .35, .14, .71, .03, .99)

example5

## participant stim_type Pr

## 1 5 exp 0.11

## 2 5 sur 0.30

## 3 6 exp 0.13

## 4 6 sur 0.50

## 5 7 exp 0.21

## 6 7 sur 0.99

## 7 8 exp 0.08

## 8 8 sur 0.35

## 9 9 exp 0.14

## 10 9 sur 0.71

## 11 10 exp 0.03

## 12 10 sur 0.99

Maybe we should start with a short recap of descriptive analyses? What’s the aim of it and what do we need it for? Well, the aim of descriptive analyses is to summarize, describe, and visualise your data, so that you and others understand it better, get an overview, and a first idea of its quality.

To get a more in-depth overview of descriptive statistics, check out the tutorials on it on pandaR! There is one for categorical and ordinally scaled variables, as well as for metric variables.

The most convenient function to get an overview is probably the summary() function. It gives you the minimum, 1st quartile, median, mean, 3rd quartile, maximum of all and only numeric variables (everything else is displayed as NA). Tip: if you have a large number of variables, add the transpose = TRUE argument for a better display.

summary(example5)

## participant stim_type Pr

## Min. : 5.0 Length:12 Min. :0.0300

## 1st Qu.: 6.0 Class :character 1st Qu.:0.1250

## Median : 7.5 Mode :character Median :0.2550

## Mean : 7.5 Mean :0.3783

## 3rd Qu.: 9.0 3rd Qu.:0.5525

## Max. :10.0 Max. :0.9900

So far so good, but this doesn’t really make sense. It would be much more interesting to look at the Pr values for both conditions separately. So let’s group the data by condition.

by(example5, example5$stim_type, summary) # It's nice to have both steps in just one line

## example5$stim_type: exp

## participant stim_type Pr

## Min. : 5.00 Length:6 Min. :0.0300

## 1st Qu.: 6.25 Class :character 1st Qu.:0.0875

## Median : 7.50 Mode :character Median :0.1200

## Mean : 7.50 Mean :0.1167

## 3rd Qu.: 8.75 3rd Qu.:0.1375

## Max. :10.00 Max. :0.2100

## ------------------------------------------------------------------------

## example5$stim_type: sur

## participant stim_type Pr

## Min. : 5.00 Length:6 Min. :0.3000

## 1st Qu.: 6.25 Class :character 1st Qu.:0.3875

## Median : 7.50 Mode :character Median :0.6050

## Mean : 7.50 Mean :0.6400

## 3rd Qu.: 8.75 3rd Qu.:0.9200

## Max. :10.00 Max. :0.9900

I just want to mention here that if you have your data in the wide format, you can skip the grouping step and do instead:

# Reshape to wide format.

library(tidyr) # A nice package for data wrangling.

example5_wide = spread(example5, stim_type, Pr)

example5_wide

## participant exp sur

## 1 5 0.11 0.30

## 2 6 0.13 0.50

## 3 7 0.21 0.99

## 4 8 0.08 0.35

## 5 9 0.14 0.71

## 6 10 0.03 0.99

# Summarize the wide format data frame.

summary(example5_wide)

## participant exp sur

## Min. : 5.00 Min. :0.0300 Min. :0.3000

## 1st Qu.: 6.25 1st Qu.:0.0875 1st Qu.:0.3875

## Median : 7.50 Median :0.1200 Median :0.6050

## Mean : 7.50 Mean :0.1167 Mean :0.6400

## 3rd Qu.: 8.75 3rd Qu.:0.1375 3rd Qu.:0.9200

## Max. :10.00 Max. :0.2100 Max. :0.9900

FYI: “wide” means that all data for each participant is in one row of the data frame, whereas in the “long” format you can have several rows for each participants, for example if you have the same variables for different measurement times.

Another possibility for inspecting your data is with the package summarytools. Especially interesting for descriptive analyses are the functions:

descr()for descriptive statisticsdfSummary()for dataframe summaries

We won’t do that here but just for you to know, you could also use:

3. freq() for frequency tables

4. ctable() for cross-tabulations

# install.packages("summarytools")

# Uncomment if you have to install it the first time. Btw, it is common courtesy to include `install.packages()` functions only commented, i.e. `#install.packages()`. Otherwise you'd expect people who use your script to either check every line for unnecessary installations or to install packages they might already have installed. Both would just waste precious time.

library(summarytools)

descr(example5_wide, stats = "common") # Most common descriptive statistics.

## Descriptive Statistics

## example5_wide

## N: 6

##

## exp participant sur

## --------------- -------- ------------- --------

## Mean 0.12 7.50 0.64

## Std.Dev 0.06 1.87 0.31

## Min 0.03 5.00 0.30

## Median 0.12 7.50 0.60

## Max 0.21 10.00 0.99

## N.Valid 6.00 6.00 6.00

## Pct.Valid 100.00 100.00 100.00

dfSummary(example5_wide)

## Data Frame Summary

## example5_wide

## Dimensions: 6 x 3

## Duplicates: 0

##

## ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

## No Variable Stats / Values Freqs (% of Valid) Graph Valid Missing

## ---- ------------- ----------------------- -------------------- -------- ---------- ---------

## 1 participant Mean (sd) : 7.5 (1.9) 5 : 1 (16.7%) III 6 0

## [numeric] min < med < max: 6 : 1 (16.7%) III (100.0%) (0.0%)

## 5 < 7.5 < 10 7 : 1 (16.7%) III

## IQR (CV) : 2.5 (0.2) 8 : 1 (16.7%) III

## 9 : 1 (16.7%) III

## 10 : 1 (16.7%) III

##

## 2 exp Mean (sd) : 0.1 (0.1) 0.03 : 1 (16.7%) III 6 0

## [numeric] min < med < max: 0.08 : 1 (16.7%) III (100.0%) (0.0%)

## 0 < 0.1 < 0.2 0.11 : 1 (16.7%) III

## IQR (CV) : 0.1 (0.5) 0.13 : 1 (16.7%) III

## 0.14 : 1 (16.7%) III

## 0.21 : 1 (16.7%) III

##

## 3 sur Mean (sd) : 0.6 (0.3) 0.30 : 1 (16.7%) III 6 0

## [numeric] min < med < max: 0.35 : 1 (16.7%) III (100.0%) (0.0%)

## 0.3 < 0.6 < 1 0.50 : 1 (16.7%) III

## IQR (CV) : 0.5 (0.5) 0.71 : 1 (16.7%) III

## 0.99 : 2 (33.3%) IIIIII

## ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In case you run into problems while installing or unpacking the summarytools() package, do not worry! Depending on your operating system, you may need to install different dependencies that allow your R to read and unpack the package. On this page you will find a detailed description of the package and all its functions, as well as hints for downloading it correctly. If you are using a Mac Computer, it might also be necessary to download a seperate program, such as XQuartz.

This could also be good practice in working on problems with your R and trying to find a suitable solution online.

Confidence intervals

Most of the time we are interested whether there is a difference between two conditions and if it is induced by our experimental manipulation. To get a first idea of if there could be a difference between the means of your two conditions, you can plot the mean of the according conditions with error bars representing the 95% confidence interval (CI). Usually we look at the 95% CI, sometimes 99%.

Short recap of what a CI is? In case of a 95% CI you have to imagine that in 95 out 100 samples, the true value of the mean will lie in between this interval.

One thing you should consider here is whether you have a between- or within-subjects design. In a within-subjects design, the test you apply usually accounts for the participant variability only and so, you don’t need the between-subjects variance. That is, the between-subjects variance has to be removed and that is done by normalizing the data. In consequence the CIs around the means appear differently and mostly smaller compared to the CIs in between-subjects designs.

For a more detailed description of how to investigate differences between two groups, check out the tutorial on tests for independent groups or this one for dependent groups. To get more information on the basics of distributions and confidence intervals, check out this tutorial.

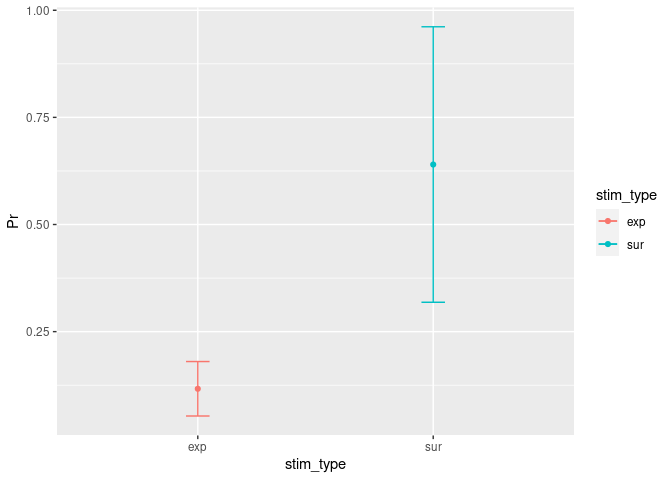

Between-subjects Design

An easy way to get all the information we need is to use the function summarySE() from the package Rmisc. It will provide you with the standard deviation, standard error of the mean, and a (default 95%) confidence interval.

# install.packages("Rmisc")

library(Rmisc)

Easyinfo = summarySE(example5, measurevar = "Pr", groupvars = "stim_type") #

Easyinfo

## stim_type N Pr sd se ci

## 1 exp 6 0.1166667 0.06055301 0.02472066 0.06354648

## 2 sur 6 0.6400000 0.30633315 0.12505999 0.32147693

In the next step you can use this very easily generated information in order to plot the mean and according CI of the two stimulus groups:

# install.packages("ggplot2")

library(ggplot2) # Load the package.

# For plotting I use here 'ggplot2'. Look at the next section (Data visualisation magic)for further information.

ggplot(Easyinfo, aes(x=stim_type, y=Pr, colour=stim_type)) + # Here you specify the data frame you want to refer to and what should be on the x and y axes...

geom_errorbar(aes(ymin=Pr-ci, ymax=Pr+ci), width=.1) + # Add here the CI.

geom_line() + # This specifies that we want a simple line.

geom_point() # But with a dot for the mean please...

## `geom_line()`: Each group consists of only one observation.

## ℹ Do you need to adjust the group aesthetic?

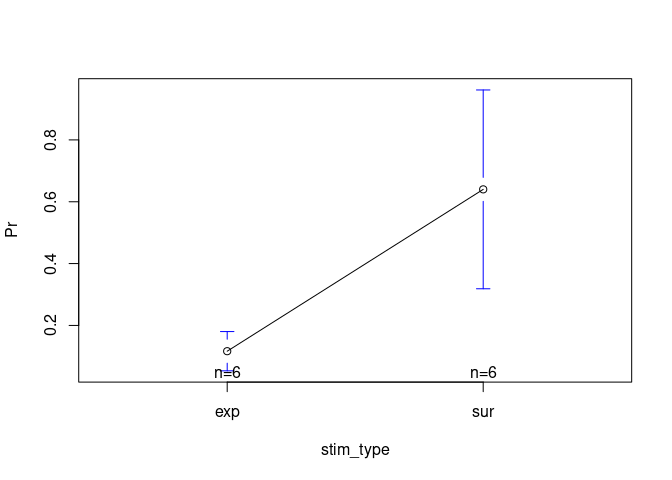

Another very easy way to get the same plot (but with less info and way uglier):

# install.packages("gplots")

library(gplots)

plotmeans(Pr ~ stim_type, data = example5)

# But this is really only for the lazy ppl - stick with the 1st version if possible.

Within-subjects Design

One way to construct CIs in within-subjects designs was proposed by Cousineau (2005) and was advanced by Morey (2005). His approach suggests to normalize the data by subtracting the participant’s mean from each observation. Then, the normalized data should be used to build confidence intervals with a similar method as for between subjects which also takes the number of observations into account.

A handy way to calculate the within-subjects CI based on Cousineau is using the function cm.ci from the package tkmisc. The only requirement here is that your data are in a wide format and contain only the values of the two conditions. In this example we can use the data frame example5_wide:

# install.packages("remotes")

# remotes::install_github("TKoscik/tk.r.misc")

library(tkmisc)

CI_within = example5_wide

CI_within = CI_within[,-1] # Remove the participant column so that only the columns with the values remain in the data frame.

CI_within = as.data.frame(cm.ci(CI_within, conf.level = 0.95, difference = TRUE)) # Apply the function and put the results in a data frame.

CI_within = tibble::rownames_to_column(CI_within, "stim_type") # Change "column 0" (contains the row names and is not really a column) to a real column. We need that later for the visualisation.

CI_within$Pr = Easyinfo$Pr # Add the mean values. Also needed for the visuals.

CI_within

## stim_type lower upper Pr

## 1 exp -0.04206084 0.2753942 0.1166667

## 2 sur 0.48127250 0.7987275 0.6400000

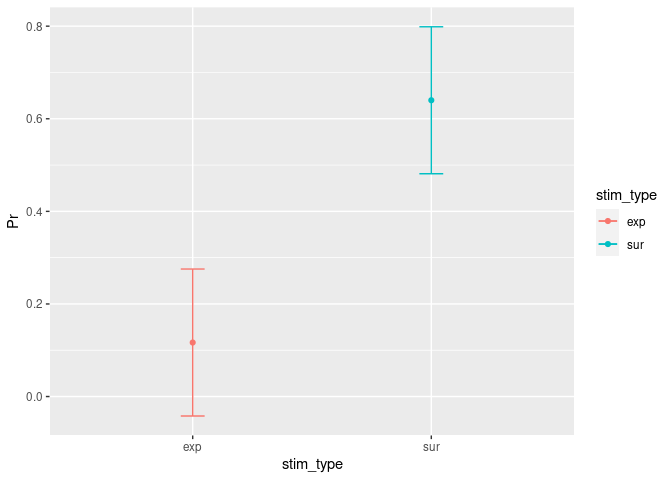

Of course we want to visually inspect these new CIs:

ggplot(CI_within, aes(x=stim_type, y=Pr, colour=stim_type)) +

geom_errorbar(aes(ymin=lower, ymax=upper), width=.1) + # Add here the CI.

geom_line() + # This specifies that we want a simple line.

geom_point() # But with a dot for the mean please...

## `geom_line()`: Each group consists of only one observation.

## ℹ Do you need to adjust the group aesthetic?

Data visualisation magic

For plotting I recommend the package ggplot2 which has many helpful functions for data visualization and it also gives you the freedom to individualize the plots and to change the parameters the way you want.

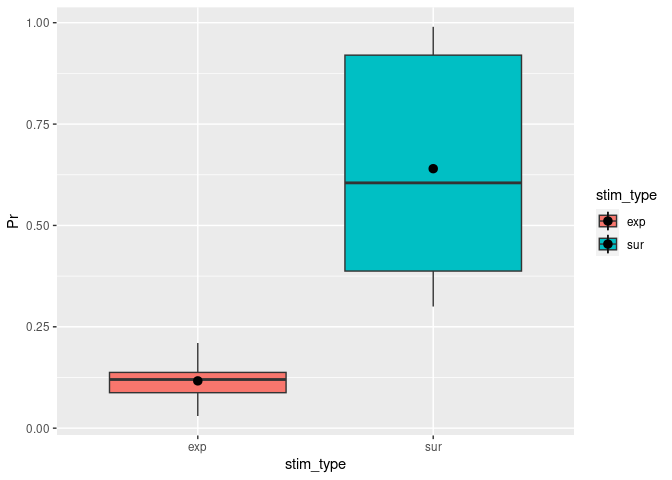

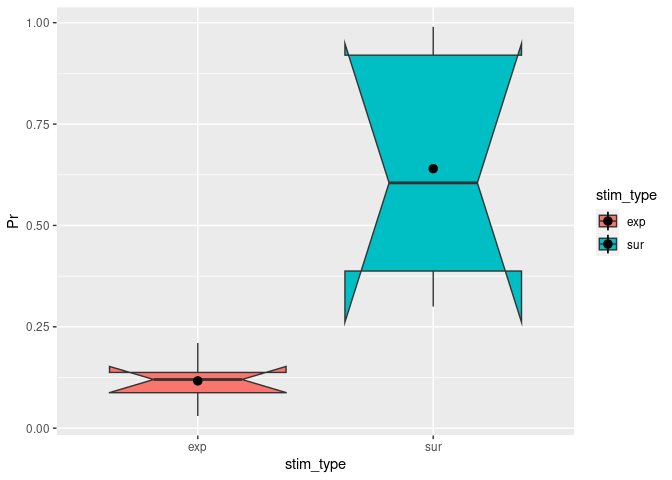

Boxplots

Other than the plot before, a boxplot will show you by default the median as well as the first and third quartiles (the 25th and 75th percentiles).

ggplot(example5, aes(stim_type, Pr, fill=stim_type)) + # `fill=` assignes different colors to the boxplots based on the condition.

geom_boxplot() + # The actual function for a boxplot.

stat_summary(fun = "mean") # It might be helpful to add the mean here as a dot.

## Warning: Removed 2 rows containing missing values (`geom_segment()`).

You can change notch to TRUE. This will give you roughly a 95% CI around the median. This is usually used to compare groups and if the boxes do not overlap you can assume that there is a difference between the two medians.

ggplot(example5, aes(stim_type, Pr, fill=stim_type)) + # `fill=` assigns different colors to the boxplots based on the condition.

geom_boxplot(notch = TRUE) + # The actual function for a boxplot.

stat_summary(fun = "mean") # It might be helpful to add the mean here as a dot.

## Notch went outside hinges

## ℹ Do you want `notch = FALSE`?

## Notch went outside hinges

## ℹ Do you want `notch = FALSE`?

## Warning: Removed 2 rows containing missing values (`geom_segment()`).

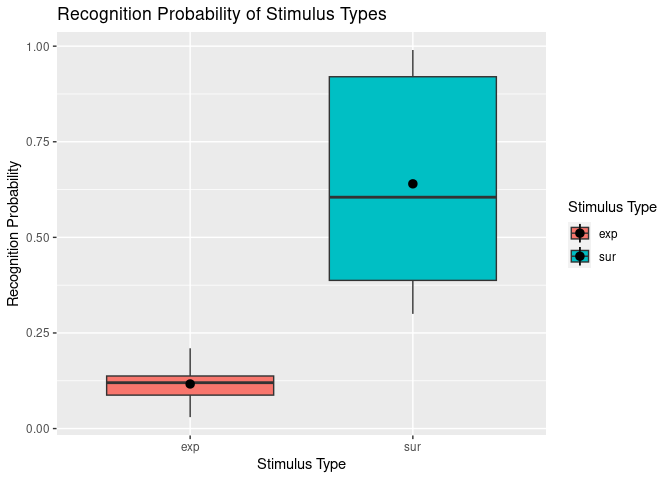

Adding titles and labels

Awesome – we’ve now got a plot clearly comparing the recognition probability (Pr) of our two different stimulus types. Now that we have that, we might also want to change the axis labels and legend titles to something prettier and more descriptive than the original variable names. We might also want to add a title.

One way of achieving this is by using ggplot’s labs() function. We can simply “add” this to our existing plotting code. For example:

ggplot(example5, aes(stim_type, Pr, fill=stim_type)) +

geom_boxplot() +

stat_summary(fun = "mean") +

labs(title = "Recognition Probability of Stimulus Types", # This bit adds the titles.

fill = "Stimulus Type",

x = "Stimulus Type",

y = "Recognition Probability"

)

## Warning: Removed 2 rows containing missing values (`geom_segment()`).

However, you will notice that this is not completely satisfactory for our x-axis and legend, since the variable stim_type that is involved here has the discrete levels “exp” and “sur” that also need to be renamed.

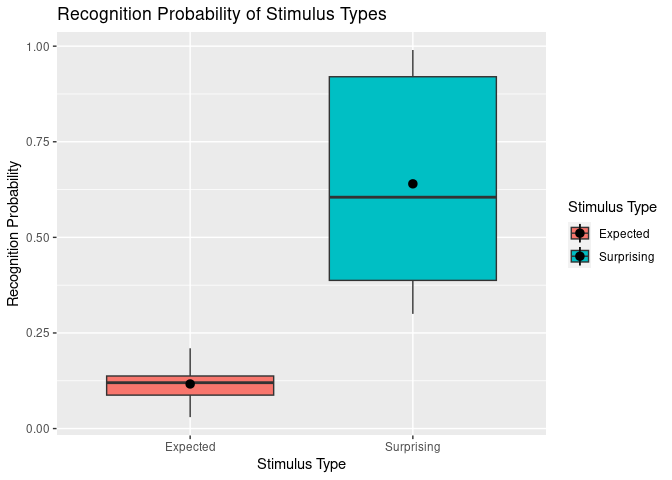

This brings us to a second method of adding labels and titles which allows more fine-tuning. Here, we use scale_x_discrete() and scale_fill_discrete() to customise our x-axis and “fill” (i.e., colour fill legend) respectively.

ggplot(example5, aes(stim_type, Pr, fill=stim_type)) +

geom_boxplot() +

stat_summary(fun = "mean") +

labs(title = "Recognition Probability of Stimulus Types",

y = "Recognition Probability") + # Keep labs() function for main title and y axis since they work fine.

scale_x_discrete(

"Stimulus Type", # x axis title

labels = c("exp" = "Expected", "sur" = "Surprising") # Change tick mark labels, using syntax OLD NAME = NEW NAME. Note that order specified here does not change order of display.

) +

scale_fill_discrete(

"Stimulus Type", # legend title

labels = c("exp" = "Expected", "sur" = "Surprising") # Change legend labels, using syntax OLD NAME = NEW NAME.

)

## Warning: Removed 2 rows containing missing values (`geom_segment()`).

Now we have plots that make reasonable sense for any reader from a quick glance, hurrah!

Of course, there are many, many other ways to customise your data visualisation to your heart’s content – including changing background colours, text size and positions of axis labels and titles, and using a colourblind-friendly colour scheme. Some of these things can be very handy, for example, to produce APA-formatted figures suitable for inclusion in theses and papers.

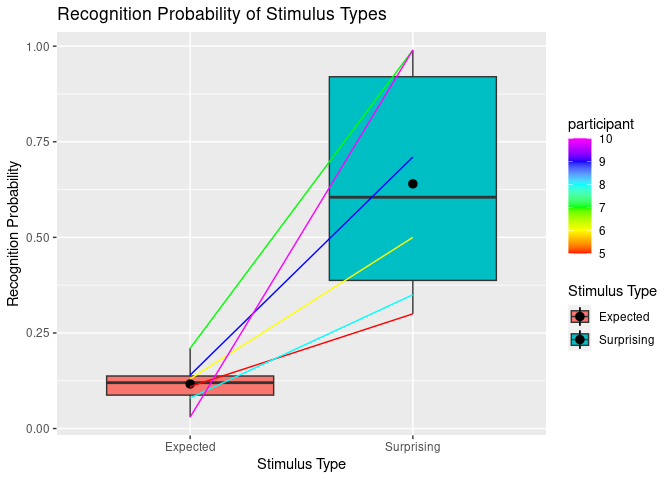

Spaghetti plots

Sometimes we want to visualise longitudinal data or we want to show which datapoints in two different conditions belong to the same participant. Therefore, we just add the geom_line() extension to what we already have created.

BUT keep in mind that too many lines (>6) can be confusing. In that case you might consider to create separate plots.

ggplot(example5, aes(stim_type, Pr, fill=stim_type)) +

geom_boxplot() +

stat_summary(fun = "mean") +

labs(title = "Recognition Probability of Stimulus Types",

y = "Recognition Probability") + # Keep labs() function for main title and y axis since they work fine.

scale_x_discrete(

"Stimulus Type", # x axis title

labels = c("exp" = "Expected", "sur" = "Surprising") # Change tick mark labels, using syntax OLD NAME = NEW NAME. Note that order specified here does not change order of display.

) +

scale_fill_discrete(

"Stimulus Type", # legend title

labels = c("exp" = "Expected", "sur" = "Surprising") # Change legend labels, using syntax OLD NAME = NEW NAME.

) +

geom_line(aes(group=participant, color=participant)) + # This is the relvant part for the spaghettis.

scale_colour_gradientn(colours=rainbow(6)) # You can specify the color palette you want to use for the lines.

## Warning: Removed 2 rows containing missing values (`geom_segment()`).

Fancy Barplots

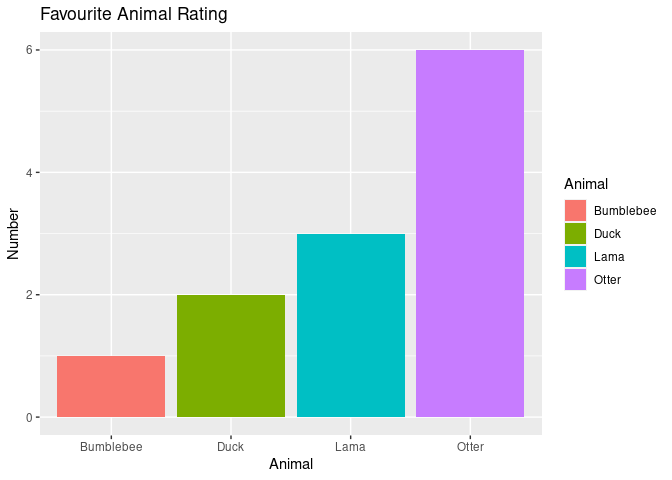

Barplots are convenient if you have for example a categorical variable and another one that represents the amount/number of something. Let’s assume we have 12 participants and we want to visualise how many of them chose an “Otter” as their favourite animal:

example6 = setNames(data.frame(matrix(ncol = 2, nrow = 12))

, c("participant", "animal"))

example6$participant = (1:12)

example6$animal = c("Otter",

"Lama",

"Otter",

"Otter",

"Lama",

"Lama",

"Otter",

"Bumblebee",

"Duck",

"Otter",

"Otter",

"Duck")

example6

## participant animal

## 1 1 Otter

## 2 2 Lama

## 3 3 Otter

## 4 4 Otter

## 5 5 Lama

## 6 6 Lama

## 7 7 Otter

## 8 8 Bumblebee

## 9 9 Duck

## 10 10 Otter

## 11 11 Otter

## 12 12 Duck

ggplot(example6, aes(animal, fill=animal)) +

geom_bar() + # This gives you the barplot.

labs(title = "Favourite Animal Rating",

y = "Number") +

scale_x_discrete(

"Animal") +

scale_fill_discrete(

"Animal")

Nice!! – naturally, the Otter is clearly the most favourite animal!

Visualizing correlations with scatter plots

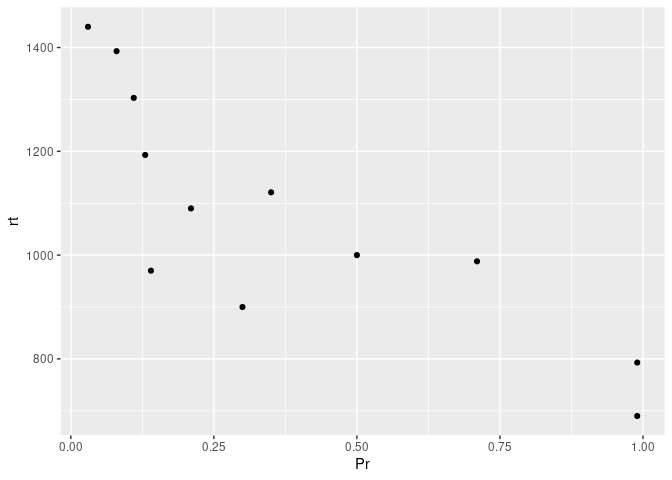

To demonstrate how we can visualize correlation, let us consider a second continuous variable – reaction time (rt) – in addition to our existing continuous variable Pr.

example7 <- example5

example7$rt <- c(1303,

900,

1193,

1000,

1090,

690,

1393,

1121,

970,

988,

1440,

793)

example7

## participant stim_type Pr rt

## 1 5 exp 0.11 1303

## 2 5 sur 0.30 900

## 3 6 exp 0.13 1193

## 4 6 sur 0.50 1000

## 5 7 exp 0.21 1090

## 6 7 sur 0.99 690

## 7 8 exp 0.08 1393

## 8 8 sur 0.35 1121

## 9 9 exp 0.14 970

## 10 9 sur 0.71 988

## 11 10 exp 0.03 1440

## 12 10 sur 0.99 793

Let’s say that we are interested in assessing whether participants’ recognition probability are correlated with their reaction time. An easy way to get a glimpse of this is using a scatterplot, by using geom_point().

ggplot(example7, aes(x=Pr , y=rt)) +

geom_point() # Makes a scatter plot using x and y variables specified in aes().

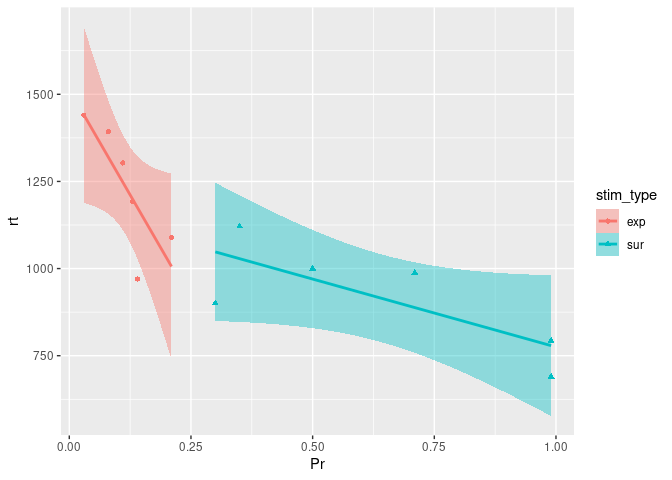

Okay, it looks like maybe something is going on here. While we could try and fit a single regression line through the above data points, it could also be more informative to see whether this relationship differs by some condition – for instance, stimulus type in our case.

ggplot(example7, aes(x=Pr, y=rt, color=stim_type, shape=stim_type)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method=lm, aes(fill=stim_type))

## `geom_smooth()` using formula = 'y ~ x'

As we can see here, this visualization is quite informative, reflecting that the correlation between recognition probability and reaction time is of the same direction between the two stimulus types, and also echoing the previous boxplots that revealed recognition probability to be higher for expected stimuli than for surprising stimuli.

Here, taking a closer look at the relationship between our two continuous variables assessed, revealed that they were of a similar nature between the levels of our condition (stimulus type). That is, for both stimulus conditions, Pr and rt were negatively correlated, as was congruent with the overall relationship suggested by our first scatterplot.

In less straightforward cases, simply assessing relationships between two variables without considering subgroups, as we’d done in the first scatterplot, can be misleading (See Simpson’s Paradox). Such scenarios highlight why it can be useful – and important – to break down your visualisation by subgroups through harnessing the power of R!

V. Inferential analysis

Before starting data analysis, it is very important to check if statistical assumptions are met. Yes, okay… but why? the answer is that the so called “parametric tests” (e.g., ANOVA, t-test, regression, etc.) require that data are within certain “parameters” in order for the analyses to be accurate. The most important assumptions are:

- Normality: data should be normally distributed.

- Homogeneity of variance: variance on each group tested should be more or less equal.

Before starting, let’s create some fake data. Let’s assume that we have reasons to believe that participants remember better images of warm food rather that images of cold food. We might want to show them images of cold and warm food (within-participants variable). In addition, we want to know whether this effect changes depending on whether a participant has already eaten or not. Therefore, we assign participants to two groups: hungry and not-hungry. Finally, we test them through a recognition test. Let’s simulate!

(!! Nerd Alert!! The following procedure shows how to simulate and thus can be skipped… unless you are very interested in it)

# Set seed.

set.seed(234634)

# First, simulate recognition for hungry: the first 30 are for cold, the other 30 for warm food.

recog_perf_H<-c(rnorm(30, mean=0.60, sd=0.13), rnorm(30, mean=0.75, sd=0.12))

# Now for not hungry.

recog_perf_nH<-c(rnorm(30, mean=0.50, sd=0.14), rnorm(30, mean=0.60, sd=0.15))

# Merge both.

recog_perf<-c(recog_perf_H, recog_perf_nH)

# Create condition variable.

condition<-rep(c("cold", "warm"), each=30, times=2)

# Participant variable.

participant<-c(rep(c(1:30), times=2), rep(31:60, times=2))

group<-rep(c("hungry", "not hungry"), each=60)

# Bind it.

data_food<-data.frame(participant, condition, recog_perf, group)

# Create also a continuous variable indicating participants' working memory performance ("wm").

# We are assuming that it is correlated to the recognition performance.

wm<-vector()

for (n in 1:length(unique(participant))){

wm[n]<-mean(data_food$recog_perf[data_food$participant==data_food$participant[n]])+rnorm(1,mean=0.10, sd=0.02)

}

# Order according to participants.

data_food<-data_food[order(data_food$participant),]

# Attach the wm variable.

data_food$wm<-rep(wm, each=2)

# Check the structure of the data.

str(data_food)

## 'data.frame': 120 obs. of 5 variables:

## $ participant: int 1 1 2 2 3 3 4 4 5 5 ...

## $ condition : chr "cold" "warm" "cold" "warm" ...

## $ recog_perf : num 0.37 0.68 0.678 0.762 0.607 ...

## $ group : chr "hungry" "hungry" "hungry" "hungry" ...

## $ wm : num 0.663 0.663 0.826 0.826 0.8 ...

# Check the format of the data:

head(data_food)

## participant condition recog_perf group wm

## 1 1 cold 0.3701675 hungry 0.6630468

## 31 1 warm 0.6795923 hungry 0.6630468

## 2 2 cold 0.6779541 hungry 0.8260525

## 32 2 warm 0.7617480 hungry 0.8260525

## 3 3 cold 0.6066051 hungry 0.8002971

## 33 3 warm 0.8200754 hungry 0.8002971

# Let us look at the data:

data_food

## participant condition recog_perf group wm

## 1 1 cold 0.3701675 hungry 0.6630468

## 31 1 warm 0.6795923 hungry 0.6630468

## 2 2 cold 0.6779541 hungry 0.8260525

## 32 2 warm 0.7617480 hungry 0.8260525

## 3 3 cold 0.6066051 hungry 0.8002971

## 33 3 warm 0.8200754 hungry 0.8002971

## 4 4 cold 0.4540464 hungry 0.6848700

## 34 4 warm 0.7102183 hungry 0.6848700

## 5 5 cold 0.4525917 hungry 0.6968984

## 35 5 warm 0.8072747 hungry 0.6968984

## 6 6 cold 0.7107697 hungry 0.7940126

## 36 6 warm 0.7325580 hungry 0.7940126

## 7 7 cold 0.4231543 hungry 0.6735239

## 37 7 warm 0.6741001 hungry 0.6735239

## 8 8 cold 0.7332302 hungry 0.7996366

## 38 8 warm 0.6361844 hungry 0.7996366

## 9 9 cold 0.6589959 hungry 0.8699979

## 39 9 warm 0.8425297 hungry 0.8699979

## 10 10 cold 0.8118603 hungry 0.7950518

## 40 10 warm 0.6340307 hungry 0.7950518

## 11 11 cold 0.7166698 hungry 0.7328982

## 41 11 warm 0.5267856 hungry 0.7328982

## 12 12 cold 0.6445626 hungry 0.7683372

## 42 12 warm 0.8025181 hungry 0.7683372

## 13 13 cold 0.5603714 hungry 0.8093576

## 43 13 warm 0.8372279 hungry 0.8093576

## 14 14 cold 0.6862972 hungry 0.8875440

## 44 14 warm 0.8588887 hungry 0.8875440

## 15 15 cold 0.6597363 hungry 0.7976466

## 45 15 warm 0.7621104 hungry 0.7976466

## 16 16 cold 0.6221724 hungry 0.7595080

## 46 16 warm 0.7029713 hungry 0.7595080

## 17 17 cold 0.6986523 hungry 0.8463840

## 47 17 warm 0.8556005 hungry 0.8463840

## 18 18 cold 0.6977015 hungry 0.8425226

## 48 18 warm 0.7773590 hungry 0.8425226

## 19 19 cold 0.5303337 hungry 0.7593470

## 49 19 warm 0.7456964 hungry 0.7593470

## 20 20 cold 0.5676298 hungry 0.6920881

## 50 20 warm 0.6067139 hungry 0.6920881

## 21 21 cold 0.3938138 hungry 0.6457582

## 51 21 warm 0.7079651 hungry 0.6457582

## 22 22 cold 0.5149368 hungry 0.7221189

## 52 22 warm 0.7385895 hungry 0.7221189

## 23 23 cold 0.4986928 hungry 0.7771958

## 53 23 warm 0.8619420 hungry 0.7771958

## 24 24 cold 0.4393526 hungry 0.6174584

## 54 24 warm 0.6565674 hungry 0.6174584

## 25 25 cold 0.5152447 hungry 0.6819865

## 55 25 warm 0.6365579 hungry 0.6819865

## 26 26 cold 0.5479081 hungry 0.7322531

## 56 26 warm 0.7232609 hungry 0.7322531

## 27 27 cold 0.7701120 hungry 0.8523281

## 57 27 warm 0.7327927 hungry 0.8523281

## 28 28 cold 0.7432171 hungry 0.9978315

## 58 28 warm 1.1242861 hungry 0.9978315

## 29 29 cold 0.7103051 hungry 0.8587518

## 59 29 warm 0.8088224 hungry 0.8587518

## 30 30 cold 0.3984270 hungry 0.7537614

## 60 30 warm 0.8910267 hungry 0.7537614

## 61 31 cold 0.6626482 not hungry 0.6299393

## 91 31 warm 0.5045346 not hungry 0.6299393

## 62 32 cold 0.5145876 not hungry 0.8531309

## 92 32 warm 0.5663960 not hungry 0.8531309

## 63 33 cold 0.5636475 not hungry 0.7841366

## 93 33 warm 0.8119157 not hungry 0.7841366

## 64 34 cold 0.5536680 not hungry 0.7192232

## 94 34 warm 0.7631179 not hungry 0.7192232

## 65 35 cold 0.7037965 not hungry 0.7208457

## 95 35 warm 0.3003196 not hungry 0.7208457

## 66 36 cold 0.5497271 not hungry 0.8038275

## 96 36 warm 0.6614769 not hungry 0.8038275

## 67 37 cold 0.5584065 not hungry 0.6287822

## 97 37 warm 0.9098799 not hungry 0.6287822

## 68 38 cold 0.6208255 not hungry 0.7695700

## 98 38 warm 0.7296477 not hungry 0.7695700

## 69 39 cold 0.6492774 not hungry 0.8753173

## 99 39 warm 0.8810639 not hungry 0.8753173

## 70 40 cold 0.5344712 not hungry 0.8335446

## 100 40 warm 0.9798494 not hungry 0.8335446

## 71 41 cold 0.3442439 not hungry 0.6993906

## 101 41 warm 0.6715204 not hungry 0.6993906

## 72 42 cold 0.4173514 not hungry 0.8510779

## 102 42 warm 0.4766666 not hungry 0.8510779

## 73 43 cold 0.4100487 not hungry 0.8055182

## 103 43 warm 0.6404090 not hungry 0.8055182

## 74 44 cold 0.4352504 not hungry 0.8917084

## 104 44 warm 0.4127080 not hungry 0.8917084

## 75 45 cold 0.6712228 not hungry 0.8168989

## 105 45 warm 0.3582321 not hungry 0.8168989

## 76 46 cold 0.3718020 not hungry 0.7671125

## 106 46 warm 0.6575176 not hungry 0.7671125

## 77 47 cold 0.6736324 not hungry 0.8866329

## 107 47 warm 0.6816603 not hungry 0.8866329

## 78 48 cold 0.5611509 not hungry 0.8291472

## 108 48 warm 0.6815224 not hungry 0.8291472

## 79 49 cold 0.4464589 not hungry 0.7247024

## 109 49 warm 0.6740202 not hungry 0.7247024

## 80 50 cold 0.4074223 not hungry 0.6494969

## 110 50 warm 0.7224195 not hungry 0.6494969

## 81 51 cold 0.5268512 not hungry 0.6877570

## 111 51 warm 0.5976927 not hungry 0.6877570

## 82 52 cold 0.5200971 not hungry 0.7275831

## 112 52 warm 0.6708792 not hungry 0.7275831

## 83 53 cold 0.6188257 not hungry 0.7826997

## 113 53 warm 0.6442603 not hungry 0.7826997

## 84 54 cold 0.4021081 not hungry 0.6371289

## 114 54 warm 0.9137242 not hungry 0.6371289

## 85 55 cold 0.4197974 not hungry 0.6798813

## 115 55 warm 0.5369418 not hungry 0.6798813

## 86 56 cold 0.3186018 not hungry 0.7523661

## 116 56 warm 0.7326065 not hungry 0.7523661

## 87 57 cold 0.6844472 not hungry 0.8608357

## 117 57 warm 0.3245837 not hungry 0.8608357

## 88 58 cold 0.6229062 not hungry 1.0451762

## 118 58 warm 0.2748781 not hungry 1.0451762

## 89 59 cold 0.3170245 not hungry 0.8247061

## 119 59 warm 0.7550980 not hungry 0.8247061

## 90 60 cold 0.5508814 not hungry 0.7728054

## 120 60 warm 0.5951913 not hungry 0.7728054

The data are organized into a “long format”, in which every row represents on condition of the variable repeated within participant. As the only repeated variable (“condition”) has only two levels, we have two rows for each participant.

Normality assumption

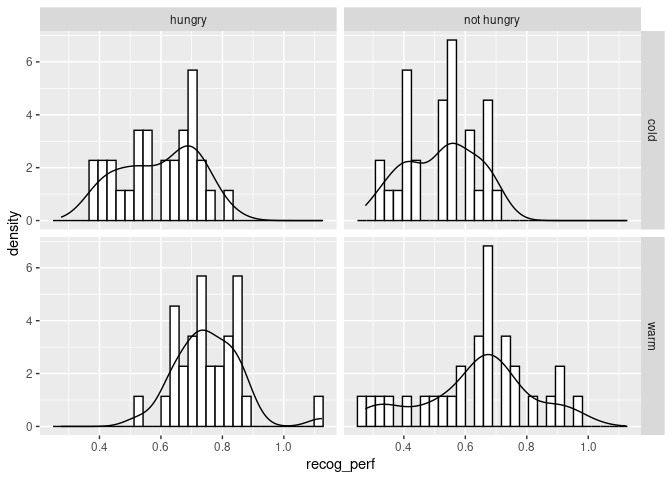

# Check the distribution of the response variable, performance (DV).

library(ggplot2)

ggplot(data_food, aes(recog_perf)) +

geom_histogram(aes(y=..density..), colour="black", fill="white") +

geom_density()+

facet_grid(condition~group)

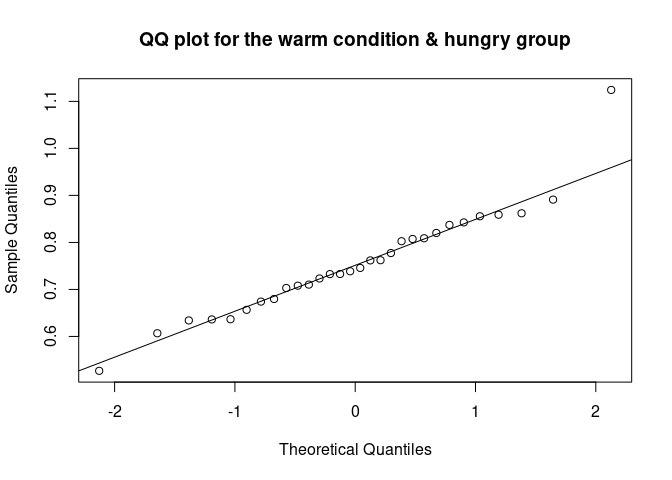

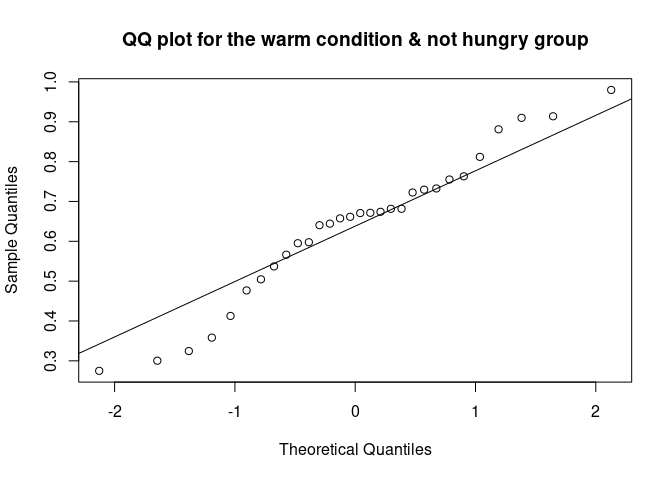

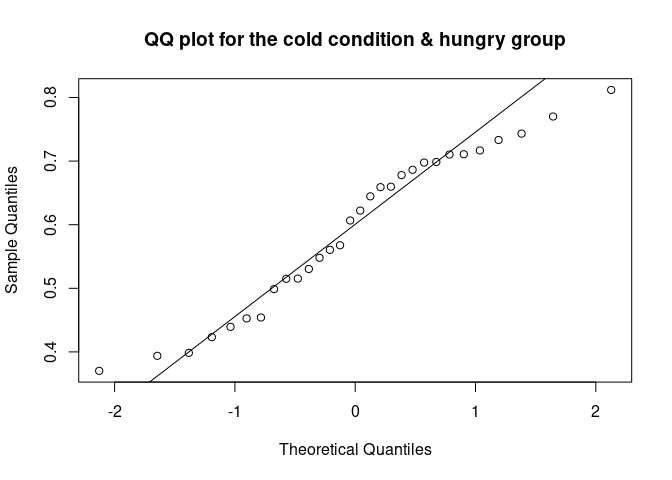

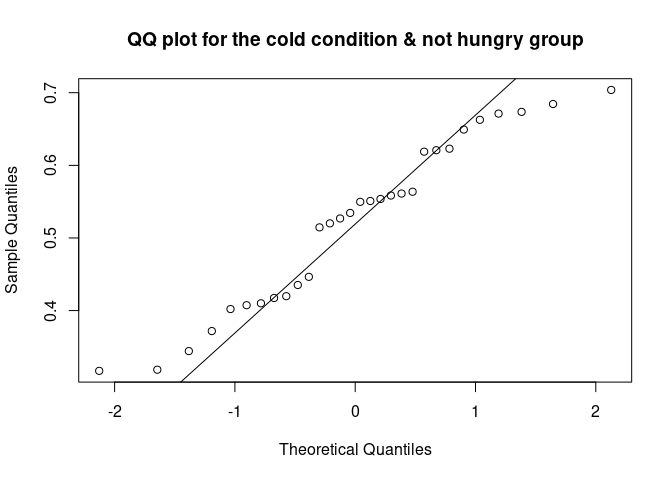

The distribution looks roughly normal. We could use a QQ plot.

The QQ plot (quantile-quantile plot) shows the correlation between the observed data and the expected values, namely the values if data were normally distributed. If observed data are normally distributed, the QQ plot looks as a straight diagonal line. Deviations from the diagonal shows deviation from normality.

qqnorm(data_food$recog_perf[data_food$condition=="warm" & data_food$group=="hungry"], main = "QQ plot for the warm condition & hungry group")

qqline(data_food$recog_perf[data_food$condition=="warm" & data_food$group=="hungry"])

qqnorm(data_food$recog_perf[data_food$condition=="warm" & data_food$group=="not hungry"], main = "QQ plot for the warm condition & not hungry group")

qqline(data_food$recog_perf[data_food$condition=="warm" & data_food$group=="not hungry"])

qqnorm(data_food$recog_perf[data_food$condition=="cold" & data_food$group=="hungry"], main = "QQ plot for the cold condition & hungry group")

qqline(data_food$recog_perf[data_food$condition=="cold" & data_food$group=="hungry"])

qqnorm(data_food$recog_perf[data_food$condition=="cold" & data_food$group=="not hungry"], main = "QQ plot for the cold condition & not hungry group")

qqline(data_food$recog_perf[data_food$condition=="cold" & data_food$group=="not hungry"])

In order to test whether the distribution deviates from a normal distribution, we can use the Shapiro-Wilk test.

This test compares the observed vales are significantly different from normally distributed values. If the test is non-significant (p > .05), the distribution of data is not different from a normal distribution.

shapiro.test(data_food$recog_perf[data_food$condition=="warm" & data_food$group=="hungry"])

##

## Shapiro-Wilk normality test

##

## data: data_food$recog_perf[data_food$condition == "warm" & data_food$group == "hungry"]

## W = 0.93816, p-value = 0.08114

shapiro.test(data_food$recog_perf[data_food$condition=="cold" & data_food$group=="hungry"])

##

## Shapiro-Wilk normality test

##

## data: data_food$recog_perf[data_food$condition == "cold" & data_food$group == "hungry"]

## W = 0.94964, p-value = 0.1653

shapiro.test(data_food$recog_perf[data_food$condition=="warm" & data_food$group=="not hungry"])

##

## Shapiro-Wilk normality test

##

## data: data_food$recog_perf[data_food$condition == "warm" & data_food$group == "not hungry"]

## W = 0.96162, p-value = 0.3405

shapiro.test(data_food$recog_perf[data_food$condition=="cold" & data_food$group=="not hungry"])

##

## Shapiro-Wilk normality test

##

## data: data_food$recog_perf[data_food$condition == "cold" & data_food$group == "not hungry"]

## W = 0.94587, p-value = 0.131

As we can see, the four tests indicate that data does not deviate from normality. In case data are not normally distributed, we can use a transformation (square, log, inverse transformation), use a non- parametric test (e.g., Spearman correlation, Mann-Whitney for comparing two means, Kruskal-Wallis for comparing multiple means), or we can use a different distribution (binomial, multinomial, etc.).

Homogeneity of variance assumption

In addition to being normally distributed, parametric tests require that the variances of different levels of one variable should be more or less equal. In other words, the variances should be “homogeneous”.

In order to check for homogeneity fo variance, we can use the Levene test.

library(car)

# We can check first if the variance differ across food condition.

leveneTest(data_food$recog_perf, data_food$condition)

## Levene's Test for Homogeneity of Variance (center = median)

## Df F value Pr(>F)

## group 1 0.5047 0.4788

## 118

# Then across hunger group.

leveneTest(data_food$recog_perf, data_food$group)

## Levene's Test for Homogeneity of Variance (center = median)

## Df F value Pr(>F)

## group 1 1.4927 0.2242

## 118

The variance seems to be homogeneous across condition and group. Similar to the Levene test, we are testing the null hypothesis, that the variances are homogenous, which is the case if our test is non-significant (p>.05). Let’s run our parametric tests!

Correlation

We can start our analysis by checking whether participants’ working memory correlates with recognition performance. For a more detailed tutorial on correlation, check out pandaR.

In order to do this, we need to work on a “wide-dataset”, where every row represents a participant. We can use the reshape() function from the reshape2 package.

library(reshape2)

##

## Attaching package: 'reshape2'

## The following object is masked from 'package:tidyr':

##

## smiths

# Create a wide dataset by aggregating performance on the participant level.

# In order to do that, we can use the reshape function.

# We need to specify the grouping variables ("idvar"), i.e. the variables that vary between participants. Those are participants' id, group, and wm. The condition that varies within participant ("timevar") is "condition".

data_food_wide<-reshape(data_food, idvar = c("participant", "group", "wm"), timevar = "condition", direction = "wide")

# Let's have a look at this dataset.

head(data_food_wide)

## participant group wm recog_perf.cold recog_perf.warm

## 1 1 hungry 0.6630468 0.3701675 0.6795923

## 2 2 hungry 0.8260525 0.6779541 0.7617480

## 3 3 hungry 0.8002971 0.6066051 0.8200754

## 4 4 hungry 0.6848700 0.4540464 0.7102183

## 5 5 hungry 0.6968984 0.4525917 0.8072747

## 6 6 hungry 0.7940126 0.7107697 0.7325580

# As you can see, we have two columns indicating "recog_perf.warm" for warm condition, and "recog_perf.cold" for cold condition.

# We want to aggregate it by averaging within participant, to have one variable indicating the recognition performance at the participant level.

# We can use the useful "rowMeans" function.

data_food_wide$recog_perf_avg<-rowMeans(data_food_wide[c("recog_perf.warm", "recog_perf.cold")])

# Check if wm is normally distributed.

shapiro.test(data_food_wide$wm)

##

## Shapiro-Wilk normality test

##

## data: data_food_wide$wm

## W = 0.96993, p-value = 0.1447

# Do the same for the aggregated recognition performance.

shapiro.test(data_food_wide$recog_perf_avg)

##

## Shapiro-Wilk normality test

##

## data: data_food_wide$recog_perf_avg

## W = 0.97621, p-value = 0.2898

# They are both normally distributed. Let's do the correlation.

cor.test(data_food_wide$recog_perf_avg, data_food_wide$wm)

##

## Pearson's product-moment correlation

##

## data: data_food_wide$recog_perf_avg and data_food_wide$wm

## t = 2.2897, df = 58, p-value = 0.02569

## alternative hypothesis: true correlation is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 0.03667974 0.50493156

## sample estimates:

## cor

## 0.2879228

There is a significant correlation between participants’ working memory and their recognition performance: Person’s r = 0.29, p < .026.

Regression

With regression we also explore relationships between variables. Unlike correlation, regression assumes that there are a response variable (or dependent variable, or outcome) and one or several predictors (or independent variables). It also allows to make prediction, thanks to the coefficients that it returns.

A more detailed tutorial on regression analysis can also be found on pandaR, where there’s a special tutorial on it.

Let’s consider our working memory - recognition relationship as a regression.

# R uses the "lm" (Linear Model) function to compute regression.

regres<-lm(recog_perf_avg~wm, data=data_food_wide)

# On the left side of the "~" there is the dependent variable, on the right the predictor(s).

# Let's have a look at the output.

summary(regres)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = recog_perf_avg ~ wm, data = data_food_wide)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -0.26837 -0.05103 0.01087 0.07627 0.23227

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 0.3690 0.1134 3.254 0.0019 **

## wm 0.3332 0.1455 2.290 0.0257 *

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.09802 on 58 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.0829, Adjusted R-squared: 0.06709

## F-statistic: 5.243 on 1 and 58 DF, p-value: 0.02569

The intercept is not informative in this case: it just tells us that when wm is 0, recognition performance is 0.369, and that this value is significantly different from 0. The estimate for “wm” tells us that after one unit change in our predictor (working memory), the response (recognition memory in %) increases by 0.33. This effect is significant.

t-test

We use t-tests to compare differences between two groups or conditions. In our food_data we have two groups and two conditions: the hungry - not hungry groups vary between participants, while the warm - cold conditions vary within-participants. Let’s test if they differ! We can start from the between-participants variable.

t.test(recog_perf_avg~group, data = data_food_wide)

##

## Welch Two Sample t-test

##

## data: recog_perf_avg by group

## t = 4.0861, df = 57.953, p-value = 0.0001366

## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means between group hungry and group not hungry is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 0.04854198 0.14177779

## sample estimates:

## mean in group hungry mean in group not hungry

## 0.6745251 0.5793652

There is a significant difference between the groups, so that the hungry group better recognized the images.

The t-test, like the ANOVA, can be considered as a special case of regression, in which the predictor (IV) is categorical.

R automatically dummy-codes the two group as “0” and “1” and returns the difference between the two.

Therefore, we could run a t-test by using the lm() function as we have already done for regression

t_test_as_reg<-lm(recog_perf_avg~group, data = data_food_wide)

summary(t_test_as_reg)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = recog_perf_avg ~ group, data = data_food_wide)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -0.155386 -0.064655 -0.009141 0.054885 0.259226

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 0.67453 0.01647 40.961 < 2e-16 ***

## groupnot hungry -0.09516 0.02329 -4.086 0.000136 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.0902 on 58 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.2235, Adjusted R-squared: 0.2101

## F-statistic: 16.7 on 1 and 58 DF, p-value: 0.0001365

# The t-value and p-value are the same as the t-test that we did before.

The only difference with the test that we ran before is that the sign of the t-value in the lm was negative. This occurs because the values that are shown refer to the difference between the “not hungry” condition and the “hungry” condition, the latter being the reference level (R automatically assigns reference level according to alphabetical order).

Now we can compare the within-participants variable: condition (warm vs. cold) In this case we have to use a paired sample t-test. We can use the t-test function and specify that the data are paired.

# Subset the variable to extract the data.

t.test(data_food_wide$recog_perf.warm, data_food_wide$recog_perf.cold, paired = TRUE)

##

## Paired t-test

##

## data: data_food_wide$recog_perf.warm and data_food_wide$recog_perf.cold

## t = 5.2523, df = 59, p-value = 2.159e-06

## alternative hypothesis: true mean difference is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 0.08604487 0.19195630

## sample estimates:

## mean difference

## 0.1390006

# This t-test is considering that each case is "paired" with the other, meaning that it is coming from the same participant.

# In order to understand the direction of the difference, let's get the means of the two conditions.

by(data_food$recog_perf, data_food$condition, FUN = mean)

## data_food$condition: cold

## [1] 0.5574449

## ------------------------------------------------------------------------

## data_food$condition: warm

## [1] 0.6964455

Warm food is remembered better than cold food. We could also consider the paired-sample t-test as a regression, but in this case would be a bit more difficult. In fact, in this case we have to take into account the dependency in the data, and this is usually done by adding random effects to the normal regression. But we can look into it later on.

One-way ANOVA

Now that we know how to compare two means, we can consider cases in which we have more than two. This is usually done with an ANOVA. To find out more about ANOVAs and contrasts, have a look at the pandaR tutorial!

(!! Nerd Alert !!) We need to create a third group in our data. The following section is not important and can be skipped, unless you are really interested.

# We can create a third group of "super hungry" people that are just starving.

recog_perf_sH<-c(rnorm(30, mean=0.40, sd=0.13), rnorm(30, mean=0.50, sd=0.12))

# Create condition variable.

condition<-rep(c("cold", "warm"), each=30)

# Participant variable.